Craving Cranes

Right now, about 6,000 Sandhill Cranes are wintering in central California, many within an easy drive from where we lived one year ago. As a corollary to “absence makes the heart grow fonder,” I’ve learned that longterm proximity can create complacency (for a partner —as well as revered places). In this instance, proximity diluted my urge to visit a wildlife reserve, where cranes seasonally aggregate.

“You live here,” my subconscious told me. “You’ve got lots of time to experience that.”

Today, from our new home in Washington, a day when the 2-hour-drive choice no longer exists, my heart aches to hear and observe Sandhill Cranes (Antigone canadensis). I can’t simply lace up my boots, grab the car keys, and go visit.

This is not to say I totally blew it (as a wildlife biologist) during our 8 years in Santa Rosa CA. I did visit the cranes twice.

In November 2017, Jim and I were on our sailboat exploring the San Joaquin-Sacramento Delta when friend Laura Neish (leader of 350 Bay Area’s climate action nonprofit), drove out to join us. The three of us left our boat bobbing at anchor in the river and drove up to the Cosumnes Reserve for a late afternoon/evening sighting of distant Sandhill Crane flocks coasting down and landing in glistening plowed rice fields.

Their yodeling calls are what I remember best. When we lived in Juneau, during their migrations north and south, we’d hear their distinct rattling calls from inside the house and rush outside to stare up at dozens of them flying overhead.

Author, mentor, and editor Sarah Rabkin (front row 2nd from left) with students at San Francisco State University’s Sierra Nevada Field Campus 2019.

In August, 2019, during Sarah Rabkin’s inspiring 5-day writing retreat, I got to observe these remarkable birds a second time in California during an evening hike with classmates. As before, I did not witness them at close range. The experience was nonetheless profound.

But then, in the next 4 years living in Santa Rosa, CA I didn’t take the initiative to say to Jim, “Hey, let’s take a day and drive out to see how the cranes are doing.”

I thought I had good reasons:

— bills to pay, laundry to do, a pile of emails to delete.

What makes this species special?

Sandhill Cranes mate for life, up to 37 years. (Whoa. . . my husband and I haven’t yet met that milestone.) Offspring remain with their parents for 9-10 months through their first southward migration.

They stand 3-4 feet tall and have wingspans 6-6.5 feet wide. In their elaborate courtship dance, a pair of birds bow and jump, flap their wings, twirl, and vocalize, a display that reinforces their bonds.

They’re also the oldest living bird species on the planet. Fossils 2.5 million-years old have been unearthed in Florida. Other bird species’ fossils date back to only 1.8 MYA.

(Main Source: The Cornell Lab’s All About Birds. Check there for a map with breeding and wintering locations and to learn more.)

How do cranes make such loud, rattling, bugle-like calls?

Something cool I learned today from a paper published in 1880 by Thomas S. Roberts, is that cranes have an extra long trachea that makes unusual bends and loops beneath their sternum, along their keel. (In the illustration the bird would be facing to the left.)

This unusual anatomy is what allows Sandhill Cranes to make such unusual, loud calls, described by naturalist Drew Lefebvre as "part elephant, part jackhammer, and part squeaky door hinge."

Beginning in high school, I’ve enjoyed showing children how to make an Origami crane out of paper. While in Mexico on our sailboat in 2013, I had so much fun with these children in San Ignacio folding cranes, including very tiny ones, that flap their wings when you tug on their tails.

The Faith of Cranes: Finding Hope and Family in Alaska is a moving memoir about a father’s struggle with the state of the world and whether to have a child. Like the author, Hank Lentfer, Sandhill Cranes also help me stay hopeful.

Writing this post, inpsired me to put a date on our calendar to visit Washington State’s Sunnyside-Snake River wildlife area next spring, where Sandhill Cranes migrating north stop on their way to their breeding grounds.

“Twenty years from now you will be more disappointed by the things you didn’t do than by the things you did.” —Mark Twain

Beth

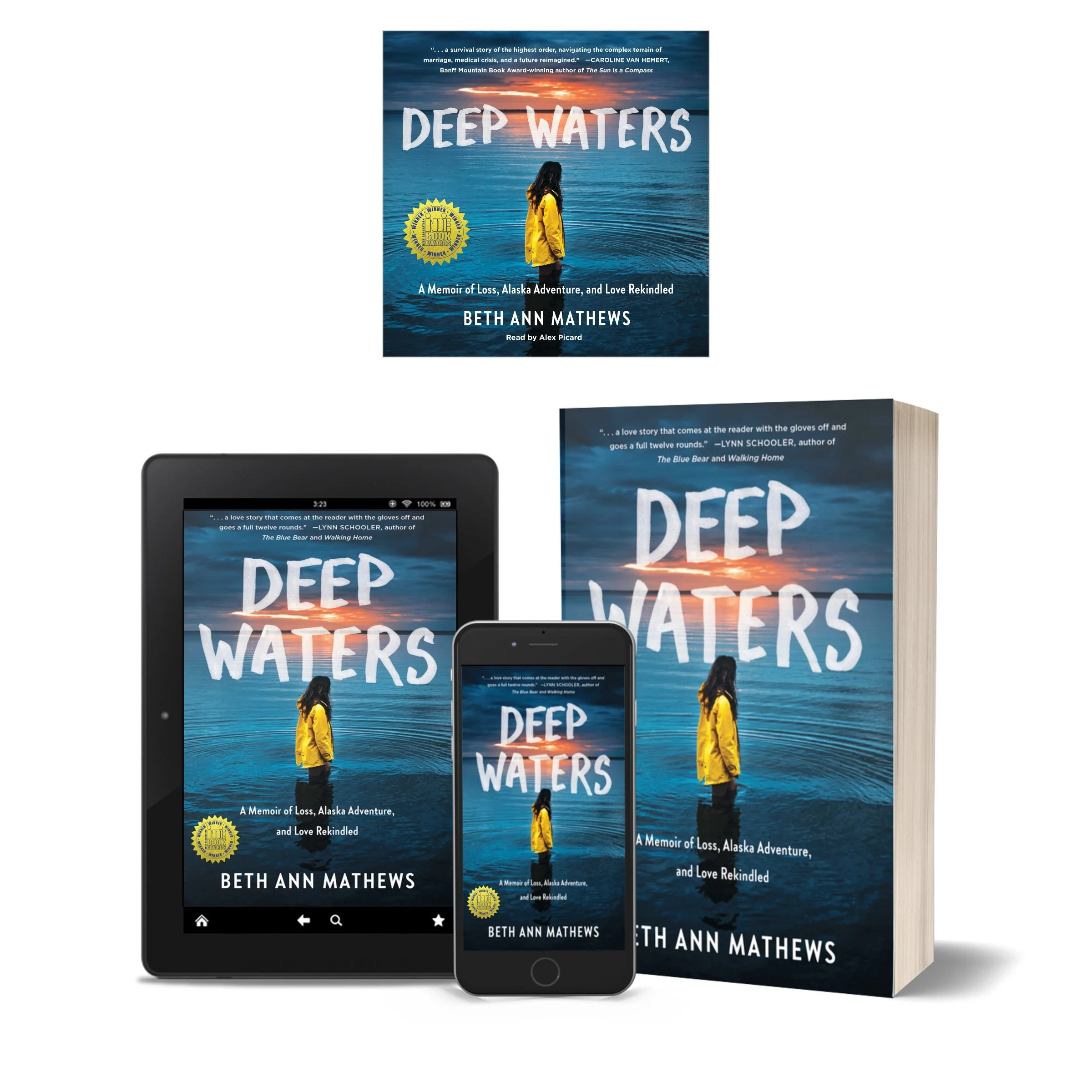

Deep Waters

A Memoir of Loss, Alaska Adventure, and Love Rekindled is now available in print, eBook, and Audiobook formats wherever you prefer to buy books online and at bookstores, and free at libraries.

P.S. Was this email forwarded to you? If so, subscribe here if you’d like to receive photo essays on wildlife, boating, and a debut authors journey.